The search for the right approach

I have been following the topic of Artificial Intelligence with great interest for some time now and it is also often present in my Master’s degree in Art History. While new guidelines at schools and universities restrict or even prohibit the use of AI tools such as ChatGPT, there is also an approach to investigate and question the way AI an its mechanisms works, and to become aware of its benefits as well as its risks.

Artists who show an interest in modern innovations approach their art precisely at the interface between science and society and thus illustrate what it means to live with AI.

In the field of learning AI, GANs (generative adversarial networks) are often used, which are modelled on the complex systems of human neural networks. Such networks are used for pattern recognition of large data sets and do not require human assistance, but instead register errors independently and learn from them. GANs in particular are also used in many ways by artists.

Examples of AI-supported art

Artistic works with these AI networks can be very different. Refik Anadol, for example, works with large-scale immersive installations, where AI processes extensive data sets from satellites. With a team of IT scientists, GAN algorithms help to generate dynamic data streams and thus explore the space between digital and physical entities. Measured brain activities can also be used as data sets. Pierre Huyghe also follows this approach. In his projects Uumwelt (Serpentine Gallery, 2018 – 2019) and After Uumwelt (La Grande Halle, 2021 – 2022) he is trying to visually represent the human thought process.

AI is also present in photography. Boris Eldagsen uses AI for an aesthetic of hyper- or surrealism and examines the human subconscious and collective fears. He won the Sony World Photography Awards in 2023, but declined it because he had acquired the award with an AI-regenerated image and wanted to draw attention to the inadequate labelling of more art that is more than just man-made. This aspect has so far been inadequately addressed by law, and although some artists advocate the rapid and spontaneous creation of art by means of AI, they also highlight the shortcomings that its use entails.

In the category Machine Visions, Trevor Paglen discusses visual training for computers by categorizing objects to ensure pattern recognition. The inaccessible and large data base for AI makes its decisions sometimes problematic and Mimi Onuoha also draws attention to people who are over- or wrongly seen by technology. Apparent prejudices of AI can thus be attributed to incomplete data principles and should be treated with caution.

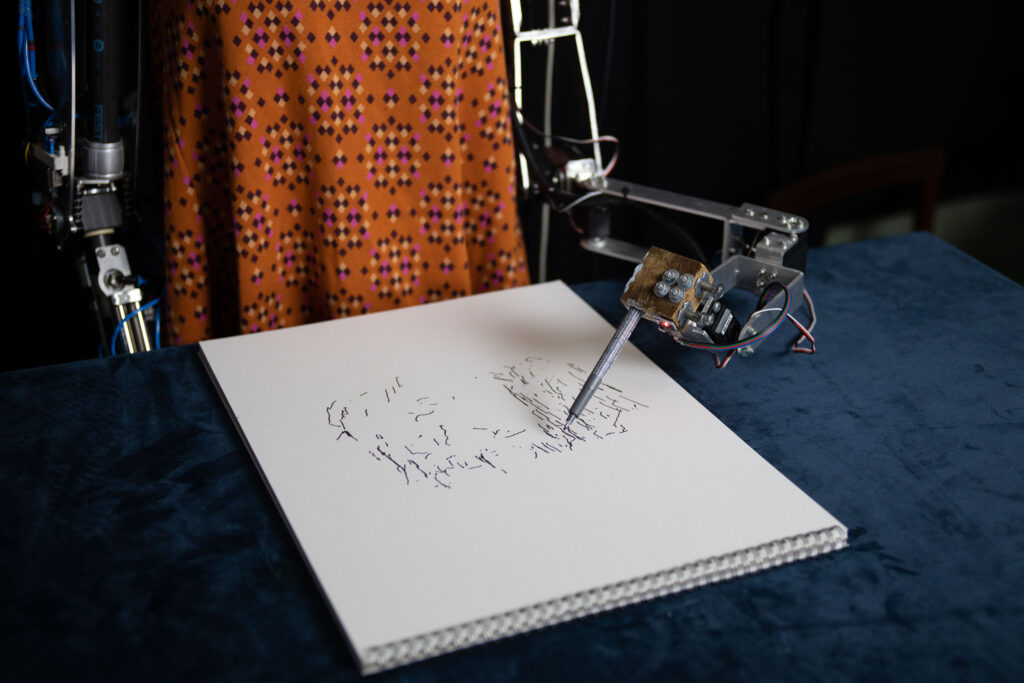

Meanwhile, in the field of art philosophy, the progressive development of AI raises the question of the possibility of a creative machine. The AI robot Ai-Da, created by Aidan Meller and Engineered Arts in 2019, is described as the world’s first ultra-realistic robot and performance artist and paints her own images using a camera in her eyes, a mechanical arm and AI algorithms. But can robots now also be called artists? Are their works actually art and the machines themselves creative, and what distinguishes human creativity from theirs?

An uncertain outlook for the future

In any case, there is no denying the continued use of AI for the future. AI is used in every mobile phone camera, it serves as an assistant and makes our technical use much easier. However, its level of self-employment continues to change, even to self-driving cars, and how far this will go is questionable. In the field of art, issues of copyright and authorship are insufficiently regulated by law, but above all, the limits of AI continue to be tested in order to expose us to its risks and side effects and to raise awareness of it.

We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us.

John Culkin